One is a Nobel Laureate, the other a Booker Prize winner. They don’t come bigger than that, do they? And yet they sit in Cartagena’s packed Teatro Adolfo Mejia to discuss the book of a French writer who died over 130 years ago.

Peruvian Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa and Englishman Julian Barnes have had great successes in their literary careers from their different corners of the world, the first writing in Spanish, the other in English. But one thing they have in common is an infatuation with Madame Bovary, the classic novel by Gustave Flaubert. Both men have written about Flaubert –Vargas Llosa, a book-length essay (Perpetual Orgy, 1975) and Barnes a novel (Flaubert’s Parrot, 1984). And now they are here, in the Colombian seaside town of Cartagena, at the Hay Literary Festival, to discuss Flaubert.

There is something about rereading Madame Bovary in Cartagena, with its colonial style architecture and narrow streets, (thanks to the Spanish influence) that is quite similar to the city of Rouen in which Emma Bovary had her escapades, this city could easily pass for the picture of Flaubertian Rouen Geoffrey Wall published in his biography, Flaubert: A Life. The clip-clops of the horse-drawn carriages ferrying tourists around the walled city could just as easily have been the soundtrack of Emma Bovary’s life. And the gilded Teatro Adolfo Mejia, where Vargas Llosa and Barnes sat to discuss Madame Bovary, could have been the theatre where Emma Bovary, bored housewife and jilted lover, met Leon and fell in love with him, yet again, opening yet another adulterous chapter in her life.

But again, why the fascination over the years since it was first published in a French newspaper in 1857 and caused so much agitation that the author was dragged to court for obscenity?

Well, for one, Madame Bovary is the story of a French house wife married to an average man of average ambitions and who, bored with the tedium of her life, indulges in affairs that thrill and eventually torture her.

And reading this book the first time, I could see Emma Bovary in many Nigerian housewives, whose husbands believe their wives, because they are quiet, are happy and content, much as Charles Bovary assumed. I could see these women whose idea of a life consisted of reading Mills and Boons or Soyayya novellas, telenovelas or kannywood movies that infuse them with false notions about reality, much as the romance novels Emma read did to her. After her first adulterous encounter with Rodolphe, Flaubert writes of Emma:

“She remembered the heroines of novels she had read, and the lyrical legion of those adulterous women began to sing in her memory with sisterly voices that enchanted her.”

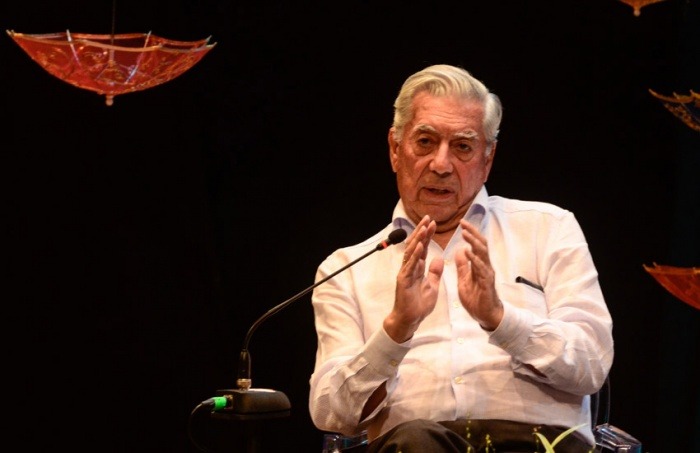

The Teatro Adolfo Mejia, splendid in all its glory, was a fitting setting for one of the biggest events of the Hay Literary Festival in Cartagena. It was packed full, all four rows of balcony included, and when the Nobel and Booker laureates mounted the podium, there was a resounding applause for them.

“I think Julian and I are the last writers who are still heavily influenced by French ideologies,” Vargas Llosa began. He is 76, Barnes is ten years younger. Twenty years ago at the Hay Festival, the two men sat down in similar circumstances to discuss Flaubert.

Nothing has changed in the last 20 years with regards to their passion for the French Writer. But since then, Vargas Llosa won the Nobel in 2010, and Barnes the Booker a year later.

“Flaubert has changed only in terms of new translations, but I think I have remained very much the same,” Barnes said.

They gushed praises for Flaubert’s work, and their passion was evident, Vargas Llosa more so. When the moderator, Colombian Journalist Marianne Ponsford ventured to suggest that Emma Bovary was a vain and simple woman, Vargas Llosa vehemently interrupted her.

“No! No! I am going to defend Emma Bovary. I am serious!” For him, Emma was a woman whose perception of reality was twisted by the books she read, romance novels that implanted false notions in her head and this coincided with the inadequacies of her husband.

“I should have warned Marianne beforehand that Mario is very much in love with Emma Bovary,” Barnes said to great laughter from the audience. And Vargas Llosa, happily conceded to this declamation with a broad smile and assenting gestures.

But if it is love he has for this fictional woman, it is a strange one. One of his favourite parts of the novel is Emma’s suicide. He reads it, he said, each time he is depressed and, while her act of poisoning herself saddens him, for some strange reason, Flaubert’s description of Emma’s tortured expression, how her face contorts in pain, always thrills Vargas Llosa and brings him back to a good frame of mind. Odd, perhaps.

Beyond contributing one of the most famous characters in literature, remarkable only in her universality because she could so easily be the woman on the street, or sitting next to you in the theatre, or perhaps the woman next door in Kano or Rome, Flaubert’s style has enchanted both men.

And moving away from their mutual admiration for Emma Bovary, Vargas Llosa said: “The idea that for fiction to be more convincing, more believable, the narrator has to vanish. That is something Flaubert introduced. For me, he was the novelist who gave the novel form.”

Before Flaubert, a meticulous writer whose attention to details and diligence to the craft has made outstanding, novels were often serialised in newspapers and served in instalments as they were being written. Flaubert worked for five years on his novel and waited until it was completed before he serialised it in the newspaper, and vehemently refused to have his novel illustrated as was the practice in those days.

And even if Flaubert dismissed his own works as a mockery of realism, Vargas Llosa and Barnes passionately dismiss such claims by the French author, citing Flaubert’s penchant to disregard even his own statements. It was almost surreal watching this authors obsess over Flaubert, even if one acknowledges, as they did, that Flaubert’s model of novel writing is something that persists till date, and this is the basis for Vargas Llosa making this bold assertion; “I think all writers, whether we like it or not, are Flaubertian.”

Vargas Llosa’s obsession is not only evident in his essay on Madame Bovary in which he gives account of his early years and the influence Flaubert has had on him, not to mention the detailed analysis of the text and themes of the novel. He is also much taken by the ‘vulgarity’ of the novel. His own novels are famed for their salacious content.

But in the case of Barnes, there is something else, apart from Madame Bovary’s vulgarity, that catches his attention.

“Madame Bovary is a novel about failure,” he said.

It is this theme of failure that has characterised his novels over the years. Most of his lead characters have been modelled somewhat like Charles Bovary; they are average, unambitious. It is this same theme that characterises his 2011 Booker Prize winning novel, The Sense of an Ending, the story of Tony Webster, an average man with average ambitions whose life is regardless characterised by failure. He failed in his relationship with his friends, failed as a husband and a father and is unsuccessful with women. And his recollection of events in his youth, the only things he can truly claim as his own, turns out to be quite the opposite of what he believed.

Whatever the case, and this is what most of the audience went away with on the night, Madame Bovary is a novel that affects different individuals on different levels; Vargas Llosa, the vulgarity and the sheer love he has for Emma; Barnes, his obsession with the theme of failure that has echoed in his novels; the average house wife, the depiction of her tedious life; and for the average man his illusion of success in the absence of any obvious shortcoming.

It is a masterpiece, as Barnes sums up; “I can’t get over how good it is. It is annoying”